I Be Brave is more than a brave story

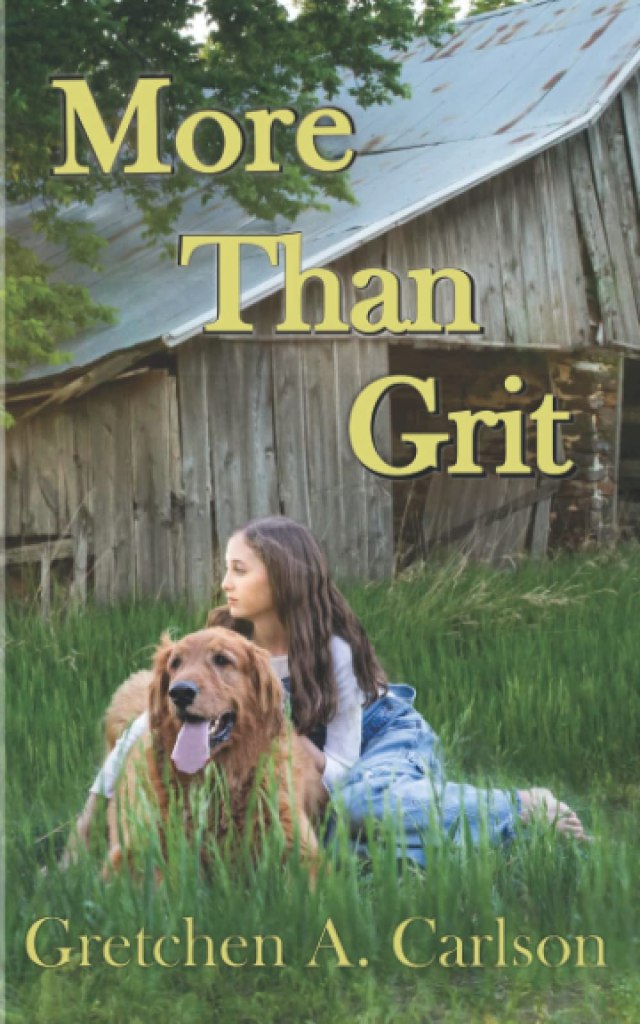

Young adult novels are a huge industry, so much so that as an adult, I’ve read more than a few. Some are worthy of their fame, many are not. One very thin genre is the historical young adult novel, and that’s one of many reasons Gretchen Carlson’s books, 2022’s More than Grit and the 2025 follow-up, I Be Brave, are wroth reading. In fact, I found it easy to picture it as a movie – if thoughtfully made by the Hallmark Channel or PBS.

(FYI – I believe you can read I Be Brave without reading More Than Grit, but because of the author’s gift of character development, reading More Than Grit first does make Sissy’s story more powerful in I Be Brave

More than Grit tells the story of a young girl’s determination to bring electricity to her family’s farm. Making a secret deal with the local grumpy “Old Man” she works to earn money that she sets aside in her quest. Set in the 1930’s, you get to experience a little of what life was like during World War II on a farm that relies on kerosene lanterns. You walk alongside Sissy as she finds a strength in herself she didn’t know she had.

I was excited when the author decided to write a follow-up to the story. Not a sequel, as the story stands on its own quite well. But it’s another step on Sissy’s journey as she continues to grow and find strength.

I Be Brave is a sweet and beautiful young adult story that perfectly captures the feelings of being young. At its heart is the friendship between Sissy and Henry; two characters whose connection grows slowly and sweetly tenderly over the course of the book. It’s a fantastic follow-up to More Than Grit which won a well-deserved award. This one is sure to be considered as well.

Told from Sissy’s perspective, the story pulls you into her world so it feels as though you are living each moment alongside her. The author’s gift for vivid, heartfelt writing makes every scene come alive. You can see the sunlight, feel the blades of grass, and picture the wheat fields from the back of a pickup truck right alongside the characters.

The author integrates the backdrop of World War II into the lives of the characters, and helps you picture how the rural Midwest experienced that time in America’s history. But it never feels forced or awkward, but purposeful and richly adds to the story.

This is more than just a story about friendship; it’s a reminder of the courage it takes to open up to others, to be honest about what you are going through, and work your way through grief in community. I Be Brave is a memorable read that will stay with you long after you turn the last page.

You can pre-order I Be Brave here.

The Promise of Christ’s Presence

Fill in the blank:

“For where two or ___ gather in my name, there am I with them”.

Did you say “two or more” or “two or three”?

Most people say “more” but a few say “three.” It can be an example of the Mandela effect. It could also be the result of pastor completely misinterpreting the passage. This phrase “two or more” has become so ubiquitous that the misquoted phrase even exists as a category on the Open Bible website. https://www.openbible.info/topics/where_two_or_more_are_gathered_in_my_name_there_will_i_be_also

I exclusively hear this verse used in the context of people gathering together for worship, prayer, study, etc… primarily used to claim the promise of God’s presence because a group has gathered. So, “more” makes sense if you think that’s what the verse means.

But it’s not. And one of the reasons we know this is because the actual verse says three not more. From Matthew 18, verse 20: “For where two or three gather in my name, there am I with them.”

Consider the theological implications of claiming God is present when “two or more are gathered.” That’s also, perhaps unintentionally, saying that God isn’t present when a person is alone. Because when this verse is mentioned, it’s most often in the context of claiming a promise. But we can also claim the promise that God is there when one person is present. This, in fact, is the truth scripture teaches.

Who can hide in secret places

(Jeremiah 23:24)

so that I cannot see them?”

declares the Lord.

“Do not I fill heaven and earth?”

declares the Lord.

During the COVID-19 shut down, people all over the world were on their couches at home trying to worship God using an online platform. Many of those people were alone. Was God not present with them, alone, in their living rooms?

Is God not with you when you are praying alone, working alone, driving in your car alone?

Historically, the Church has been quite good at taking verses out of context. With the best of intentions, its simply a misunderstanding. With the most egregious, it’s to prove a belief already held, choosing to manipulate actual truth, attempting to conform it to make a point with an outside source.

The theological implications of continuing to use this verse for this purpose of feeling better when there is a small group is also to say that God is not omnipresent. In an culture where the literal reading of Scripture is more prevelant than not (that’s a post for another time) there isn’t much other conclusion we can come to when we read it that way. If we read it flatly, out of context, it’s also saying what it’s not saying; that God isn’t present when there is only one person. And the rest of Scripture does not support this at all.

Nothing in all creation is hidden from God’s sight. Everything is uncovered and laid bare before the eyes of him to whom we must give account.

(Hebrews 4:13)

So how are we to use and understand this verse? This should be obvious, but it’s clearly not since this verse is misused so frequently: you start with reading the verses before and after it. In the verse after, it starts with “Then Peter came…” With the use of the word “Then” we conclude there is natural break, ending the section in verse 20. For proper context, we look to the verses right before it. Which isn’t related to worship or prayer meetings AT ALL, but rather instruction for going to a person who you feel has wronged you, and then if needed, bringing others into the conversation.

The Greek word that is translated to “three” is τρεῖς. And it’s key here, because it doesn’t infer “more”, but is a direct reference to the need for two or three people in the case of dealing with conflict. Jesus says in verse 16, instructing us how to handle people who’ve sinned against us, by saying, “But if they will not listen, take one or two others along,”

Thus, where “two or three” come from. Jesus is teaching that when a person has sinned and they need to be confronted in that sin, taking one or two others along when they don’t repent after you have spoken to them is the next step. And if those one or two agree with you, Jesus is assuring us that he is present when two or three agree (v. 19 affirms this as well).

He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.

(colossians 1:17)

I understand the desire to use a broader brush where this verse is concerned. It’s not like it technically untrue. But is it untrue that he isn’t present when less are worshipping him. Correcting the use of this verse, especially when it communicates something that isn’t true, is more important than wanting to use it as a quick and almost pithy phrase to claim a promise. Christ is present in worship where multiple people are gathered. That’s because he is everywhere, all the time, no matter how many are together, from one to one thousand and beyond. To claim the promise of Christ’s presence by using the Matthew 18 verse isn’t helpful, because of the implied reverse. You can use any of the verses I’ve listed here in this post to make this point.

His eyes are on the ways of mortals;

(Job 34:21)

he sees their every step.

We do not need to claim the promise of God being present ONCE we do something.

We can claim that promise because of who God is, not because of what we have done. We don’t need to gather two or three so Christ will be present in worship. He’s already there.

The Power of Hope

I started a new sermon series this week at my current church, where I’m the interim pastor. I’m calling it “The Remedy of Hope” and it’s been interesting as I’ve prepared for the series; choosing passages and planning the structure of it. Interesting in that it’s simply not like me to be so… positive.

I say this with a caveat: if you know me and have met me, I’m a joyful person. I have Jesus and my hope is in Him. Yet I was also wired with “worst-case” personality syndrome, which I find myself leaning into more naturally than I do into a hopeful one. I’m a 4 on the Enneagram, which I’m told is the Eeyore of personalities.

I was also wired with “worst-case” personality syndrome, which I find myself leaning into more naturally than I do into a hopeful one.

There was a scientist names Curt Richter, in the 1950s, who ran an experiment on rats as he was studying psychology.

And morbidly, he took a bunch of rats and put them in buckets full of water to see how long it would take them to drown. This is a famous experiment! He used domesticated rats and wild rats – each time observing that all of them drowned within a few minutes, even though wild rats are far more resilient out in the world. He expected them to survive longer. But no, both kinds died after just a few minutes. He decided to take his experiment further. He took the same kinds of rats and this time, he noted the moment at which they gave up then, just before they were about to die, he rescued them. He saved them, held them for a while and helped them recover.

He then placed them back into the buckets and started the experiment all over again. When the rats were placed back into the water they swam and swam, for much longer than they had the first time they were placed in the buckets. The only thing that had changed was that they had been saved before, so had hope this time.

When the rats learned that they were not doomed, that the situation was not lost, that there might be a helping hand – that they had a reason to keep swimming—they did. They did not give up. They kept going.

By the end of his experiment the rats swam for almost 3 days before they died, compared to the few minutes they swam when they didn’t realize they might be saved.

So apparently hope does that.

I fight against my Eeyore nature when thing are hard, uncertain, complicated, or messy. And this only shifted in my once it was pointed out that this was my default. When I make this shift in my mindset, and when I lead as a pastor from that mindset, I’m amazed at the difference it makes in my own heart and in the attitude of those around me. Because here’s the rub: who am I to limit God? Why should I focus on what is merely attainable when I simply don’t know what God has planned?

Hope is a powerful thing.

Why should I focus on what is merely attainable when I simply don’t know what God has planned?

I don’t want to discount practicality, nor have I any interest into veering off into prosperity gospel territory. There will be no “name it and claim it” declarations here. I’m seeking to find the right balance of Jesus in the garden: willing to ask for the big and impossible thing, but also to submit to the sovereign will of my Heavenly Father.

I’ve written a lot about expectations over the years (click the topic link “expectations” on your right to scan through them) and it’s important to note how hope and expectations are deeply connected. No one like disappointment, and I think that’s precisely why it’s hard for us to hope. But I also find myself less disappointed when things don’t happen who I hope them to, because I know and trust in who God is. And much of that is surrendering to the truth that He allows what He allows and withholds what He withholds. I almost never understand why (expect maybe years later) but when I understand His sovereign will within the foundational truth He is a good and loving God, who loves me with a hesed love, I become much more willing to accept what I do not understand.

When I understand His sovereign will within the foundational truth He is a good and loving God, who loves me with a hesed love, I become much more willing to accept what I do not understand.

art and emotions

This is an unusual topic for me to post about, but as I came across this video on my social media timeline several times this week, I eventually relented and watched it. And it profoundly affected me. It was worth exploring why.

As a musician and a writer, I suppose I’ve always considered myself more on the artistic side. I ride the line between being creative vs. being someone who creates, and so sometimes I feel like an imposter if I call myself an “artist.” But I do consider myself someone who considers beauty and art an important art of our lives, which I believe is one of the reasons this video has struck a chord in me. (FYI, this video is from several years ago, it has just now come into my orbit.)

I don’t know anything about Hayao Miyazaki, but I’m thinking he and I have a type of soul connection based on his response to this AI technology. Aside from the grotesque movement that occur in movies I don’t watch, he seems to innately understand where art comes from.

And it comes from pain.

Perhaps this makes you uncomfortable. In my experience, usually the things that makes us uncomfortable are worth contemplating. That’s how we learn. Other than be afraid of the uncomfortable, we are much better coming o our uncomfortableness with curiosity.

If art comes from pain, that means pain is a reality of this world that has a type of power over us. Anything that has power over us threatens our desire to be in control of our lives.

If art comes from pain, that means pain is a reality of this world that has a type of power over us. Anything that has power over us threatens our desire to be in control of our lives.

We can spend a great deal of time trying to control our universe, but if you’ve lived any life at all you know and understand that this broken world doesn’t allow us to control everything. Even if we did live in a perfect world, we would still live in the Kingdom of God, which is controlled by Him and not us.

This, of course, doesn’t mean our decisions don’t matter, they just don’t determine the future (a paraphrase from this Tim Keller sermon). But the fact that our decisions matter is exactly why Miyazaki is responded the way he is to this AI technology.

As a writer, my most powerful and profound work has come from places of pain. See this piece or this piece I wrote for Fathom Magazine. These are pieces I’m very proud of. But creating them was painful. Living them was also painful.

I also came out of the other side a different and dare I say, better, person.

Not all pain does this, but I do believe God desires to create beauty out of the mess of this sinful world. Whether it’s how I’ve been treated as a female pastor or how someone criticized the way I laugh 20 years ago, I’m a different person because of the pain they caused me. By God’s grace, I’m not only different but more like Him.

“Everything is permissible but not everything is beneficial.” (1 Corinthians 10:23) With everything that is created, spoken, “put out into the world” if you will, we should perhaps be asking “What are the implications of this when lived out? When we put this created thing out into the world?”

This is what, I believe, Miyazaki is willing to consider in this moment of movement forward in the industry. He may not be sure, especially so soon after the initial presentation, of being able to fully understand why he feels the way he does about this technology. But the implication is clear: the art without pain isn’t art he is willing to be part of. And that lived out is “art” without human emotions is an affront to life itself for him.

“What are the lived out implications of creating a machine that creates art like a human being would?”

This poses an important question: what is life without emotions? In a tangible sense, for a person, it looks like a sociopath, who does not feel guilt for the destruction they cause. There are other psychological personality disorders that do not experience emotion the way most people do, but this is the mostly widely used label I can put on a lived-out scenario of what I’m talking about. When one manipulates, controls, and destroys without concerns for the other, the reason it’s harmful is because it assaults the humanity of the person. For a Christian, you could say that it assaults the Imago Dei in them.

When I volunteered at a local elementary school, one of the roles I had was teaching character lessons to the kids in partnership with the school counselor. After my first year of teaching the kids about honesty, responsibility, kindness and the like, I realized something important. The reason why we don’t treat others well is because we don’t think they matter as much as we do. We spent a lot time talking to kids about not bullying because “it’s not nice.”

But it’s so much more than that. Kids need to understand why it’s not nice. Not just that it’s mean. Once I realized this, I started ending each of my lessons with the phrase, “We’re teaching you this because you matter. And it’s important you understand that every other person in the room matters, too.

Which is why it’s so important to ask, “What are the lived out implications of creating a machine that creates art like a human being would?” If we are going to start replacing humans with machines, and those machines create things (such as movie animation, art, etc) intended to make us feel… then what can it make us feel if the created itself has no emotions? Will we come to a place of not seeing value in others, because we’ve removed emotions from what we create?

It’s far too easy to separate the humanity from the person when emotions are not involved.

Which is why I cannot help but ask myself, as technology moves forward with the goal of replacing what humans functionally do, the following question:

How long will it be, if art isn’t born from emotions, before we ourselves forget how to feel?